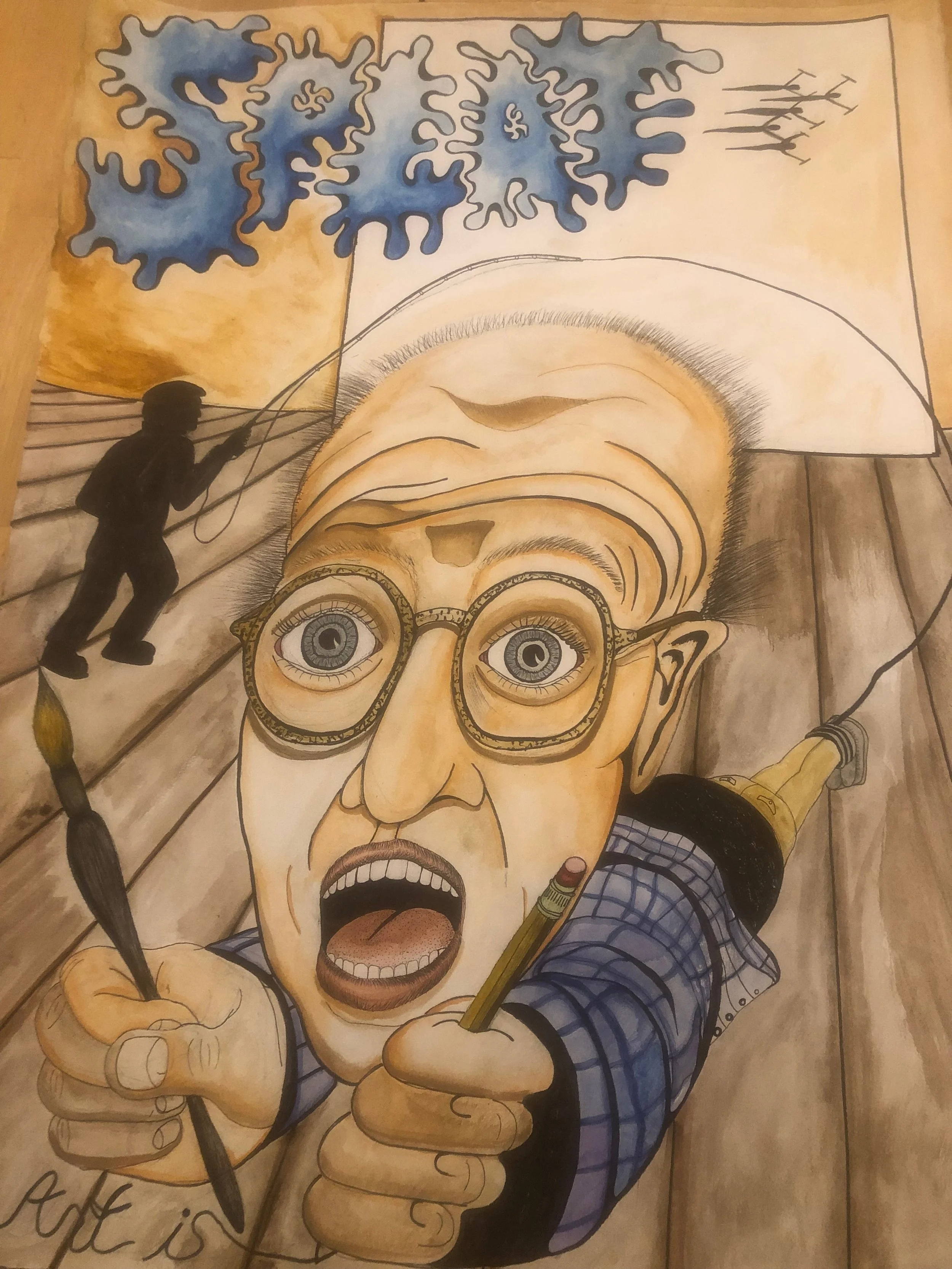

Ben Miller

The Critic, 2024

Watercolor on paper

You Missed the Mark, Jerry

A Letter to Art Critic Jerry Saltz by Gary Snyder

Jerry –

We have known each other since the 1980s when I had an art gallery in Princeton, New Jersey, and you were helping my client build a contemporary collection. I remember negotiating for Jeff Koons’ ‘Woman In Tub’ which you recommended to my client - quite a good investment!!

I believe you followed my program of modern American art during the twenty years I had galleries in New York City, and the successes I had rediscovering historically rooted artists such as Janet Sobel, Vivian Springford, Thomas Downing, Nicholas Krushenick, Al Loving, and more.

And I know you are familiar with the artist Ben Miller I have been championing in Montana for the last five years, as you have been kind enough to ‘like’ many of my Instagram posts at @garysnyderfineart .

I heard anecdotally that you do not believe Ben’s art will be successful because he paints with a fly rod, and painting with a fly rod is too much of a gimmick. You have always been an open and honest critic, so I presume you believe your position.

It surprises me that someone who can recognize significant new mark-making in art – as evidenced by your quote on Pollock and Richter…

“Just as Pollock used the drip to meld process and product, Richter 'found' and used the smudge and the blur to ravish the eye, creating works of psychic and physical power.”

…won’t take the time to recognize Ben Miller’s marks as new and important, just because he paints with a fly rod. I am also curious why Rebecca Horn’s “machines”, Maurizio Cattelan’s “guns”, Kazuo Shiraga’s “foot”, and other unconventional ways of making art, are not also “gimmicky”.

If I am right about Ben Miller, his marks may be seen as significant as Jackson Pollock’s drips, Morris Louis’s pours, Helen Frankenthaler’s stains, and Gerhardt Richter’s smudges.

Let me start by making an argument for the importance of Ben Miller’s marks, which is part of a larger argument for the importance of Ben Miller’s paintings.

Ben uses a fly rod as a ‘paint brush’, casting in the same way as one would if they were fly fishing, but instead of a conventional fly on the end of a line, Ben attaches to the end of the line what he calls “fly brushes”. He uses materials such as twine, or yarn, or nylon, or leather, shaped so that when paint is applied, and then cast on to plexiglass, a mark is made that relates to the shape of the fly brush.

Each of these fly brushes is named by Ben, drawn carefully into a notebook and surrounded by text discussing the aerodynamics of the fly brush and the intent of the mark it will make.

Note how different this is from Pollock, Louis or Frankenthaler – pigment is not just material when it hits canvas, it is already shaped and animated. So much about this is interesting – for one, it is consistent with fly fishing, as the idea in fly fishing is to create an ‘artificial fly’ that tricks the fish into thinking it is an actual insect - more about fishing later… It also upsets the Greenbergian apple cart, suggesting that the stuff of the universe is not material but animate.

Then there is the actual technique and physics of casting, and the fact that Miller stands about 15 feet away from the plexiglass surface, his 8-to-11-foot rod casting an 8 foot line back – up to twenty feet between the back cast and the mark made with the forward cast.

Pollock’s genius notwithstanding, one can imagine someone trying to copy his technique and being able to roughly mimic it. Or copying a Richter smudge, as you know well. It would take far longer for someone to master the fly cast technique, especially the way a fly cast master painter like Ben Miller, after years of practice (he has been fly fishing since the age of eight and fly cast painting for the last six years), with over 150 paintings under his belt, is able to hit different areas of the surface with varied effects.

If you watch video of Pollock, he often paints with a paint stirring stick, and you can see his hand and arm movements are not dissimilar to a fly cast motion. He makes a back motion, then a forward motion, flinging drops of paint off the stick from about five feet. If you replace the paint stirring stick with a fly rod, a similar hand and arm motion is used, although arguably far further developed with a fly cast.

Let’s talk for a moment about velocity. Do you know why a whip cracks? The crack a whip makes is produced when a section of the whip moves faster than the speed of sound creating a small sonic boom. Ben is able to cast the fly brush so that it can hit the plexiglass at over 80 miles per hour. Each mark is as singular as a snowflake – except in this case each snowflake, each mark, is controlled to some extent by a range of factors – shape and material of fly brush, the paint colors applied to the fly brush, velocity of the cast (like a pitcher, he can throw a fastball or a knuckle ball, side arm, overhead, and, like a Japanese swordsman with yokemenuchi hantai, come from the opposite direction.) Sometimes he does what he calls a “false cast” – just as the fly brush is about to hit the plexiglass, he pulls back, so, like Pollock, all he gets is the spray and drops of flying paint.

There is also an argument to be made - powerfully related to the importance of Miller’s marks - that the algorithm of the cast is profound, and relates to our world in ways similar to waves ebbing and flowing, grain moving in the wind, the breath of a master meditator, or perhaps the movement of quarks.

The physics and complexity of a fly cast has been studied by physicists – just a portion of one of those studies is as follows:

“~.(----..l....C_"-->-.(~ /

Fig. 1. Flyline motion during overhead cast.

velocity decreases and the flyline travels free of the rod motion. The horizontal flyline velocity equals the maxi- mum horizontal component of the rod tip velocity. How- ever, since the end of the line is attached to the rod tip, that end will have essentially zero velocity. Thus, the attached line is stationary while the remaining line is traveling, and a loop is formed at the interface between these two segments of line. Since the relative length of each portion of line will change during the cast, the loop will travel down the line like a wave until it reaches the free end of the line carrying the fly. The loop unrolls, the line straightens, and the cast is complete.

The work-energy method is employed to determine the velocity of the traveling line and the attached fly. The nomenclature and variables in the model are illustrated in Fig. 2. The cast begins with a loop of diameter, initial line length Lo, initial mass mo, and initial velocity Vo' In the absence of viscous drag, conservation of kinetic energy predicts the velocity of the traveling line at any time t by

(1I2)m(t)V(t)2= (1I2)moV6. (1)

The mass of the traveling line m(t) will diminish as the cast progresses since L (t) decreases. The simple relationship

m(t) =pL(t) , (2)

where p is the line mass per unit length, can be used to predict.m (t) if the line has uniform diameter throughout. The silk flylines used for years by flycasters are close to uniform diameter and would well fit this model. But modern polymer technology has produced flylines that have variously tapered sections along their length. These lines are used by the predominance of flycasters because of cost and performance. For these tapered lines, the volume of the traveling line must be computed and line density used. It should also be noted that the mass of the fly mf , which is small but finite, must be added so that

m(t) =pL(t) +mf · (3)

The effects of air friction are not negligible and should be included. Since viscous drag is dissipative, the kinetic energy of the flyline during a cast will continuously decrease as work is done by the line on the surrounding air. Hence, the work-energy equation for the flyline is

v -

'====;:===:::J A -:::====:::;====5:t< ,~X

(1!2)m(t)V(t)2= (1I2)moV6 -

rS(t)

Jo F(t)ds.

(4)

Fig. 3. Simplified flyline for drag calculations.

Also

-tis = V(t)dt, (5)

S(t)= JV(t)dt, (6) L(t) = (1I2)S(t) . (7)

The drag force F(t) acting on the flyline can be written as

n

F(t) = L [(CD A);(1I2)Pa V(t)7] , (8)

;=1

where it is assumed that the flyline fly system can be separated into n distinguishable segments. Then for each segment i, CD is the drag coefficient, A is the characteristic surface area, V(t) is the instantaneous velocity (assuming zero velocity for the surrounding air), and pa is air density. The major distinguishable parts of the cast flyline that contribute to the viscous drag are the loop, the traveling line, and the fly. Certain simplifying assumptions are necessary for each of these parts of these parts to allow calculation of representative drag coefficients and surface areas. The essence of each assumption is illustrated in Fig. 3, where a tapered line is modeled to indicate the effective diameters used for each segment.

The loop is modeled as a uniform cylinder in crossflow, with length equal to the loop diameter and cylinder diameter equal to the average diameter of the taper contained within the loop. The drag coefficient for a cylinder in cross- flow is approximately constant and equal to 1.0 in the range of Reynolds ambers that occur in this model. The velocity of the loop is one-half that of the traveling line, so

ViooP =(112)V(t). (9)

The modeling of the rolling loop as a cylinder in cross- flow is a major simplification but is employed for lack of a more representative model. As is demonstrated later, air drag on the loop dominates the total viscous effect, so this aspect of the model could undoubtedly benefit from refinement.

The traveling line is modeled as a long cylinder parallel to the flow, and the drag coefficient correlation recommended by White for this condition is

CD = 0.0015 + [0.30 +0.015 (L !r)0.4 ]Rei 1/3 (to) 69

The average diameter of the traveling line taper is used to calculate the L r ratio as well as the line surface area. The fly is modeled as a sphere with effective diameter of 1.5 cm, which is representative of a typically bushy, dry fly. In the range of Reynolds numbers that apply to the fly, the drag coefficient for a sphere is fairly constant and CD = 0.4 is used here. Fly drag proves to be a small contribution to

LOOP

v:-tV(t)~

~ V: V(t)

Fig. 2. Flyline model nomenclature.

t o e - - - - - L(t )-----.~I ~r_--~-~~-----~FLY

TRAVELING LI N E

for 10 <ReL <10 • “

On to the fly rod.

It is believed that early humans began fishing for food as long as 40,000 years ago. The use of fishing rods can be traced back to over 4,000 years ago. The first rods were made from six-foot long bamboo, hazel shoots, or sections of a thin tapered flexible wood with a horsehair line attached. A simple hook was tied to the end of the line.

The following is a quote on the development of the fly rod:

“In the 1600s, fishing tackle was improved. A wire loop was attached to the end of the rod allowing for a running line, helpful for casting and playing a hooked fish. The fishing reel was developed; a wooden spool with a metal ring that fitted over the fisherman’s thumb. Rods were designed in sections so that they could be easily taken apart and carried from one place to another, Charles Kirby improved how fishhooks were designed and made, and gut string line was developed.

By 1770, a rod with guides along its length for the line and a reel was in use. The first true reel was a geared reel attached under the rod in which a turn of the handle moved the spool several revolutions. Rods also were made better with the use of tough elastic straight-grained woods such as lancewood from South America and bamboo from India.

In the late 1800s, rods made were stronger and thinner by gluing together several strips of bamboo. Line made of silk covered with coats of oxidized linseed oil replaced horsehair, allowing for longer casts. By the early 1900s, fishing rods were now made with fiberglass. Fishing reels were improved, and spin casting reels became popular. In the 1930s, nylon monofilament was developed, and in the mid 1940s braided and synthetic lines were being produced. By the late 1960s, rods were being made with carbon fiber allowing them to be stronger, shorter, and lighter. Plastics began to replace wood for artificial casting lures.”

Ben Miller writes a great deal about his fly cast painting. He talks about a fly rod as a form of a paint brush, just much further evolved:

“Painters in the past have used a remarkably similar paint brush to make their marks, but [it is nothing like] how a fly rod can send materials with ever increasing momentum in an arching loop with the smallest strand of connectivity to a presentation at the end of its line of travel. Give me this “paint brush” with the carbon fiber, nano technology and options of fuji guides and cigar grip, differentiations of tapers in the handles from the local artisan shop. Paint brush options …have not changed or evolved anywhere close to the complexities of a fly rod. The effort and evolution put into a paint brush is nowhere close to the craftsmanship and technology put into a fly rod.”

Looking at the complexity of the cast, the human ingenuity in creating a fly rod and the possibility that it can be a form of paint brush, the Calder-esque invention of myriad fly brushes designed to aerodynamically move through the air, the absolute brand-newness of the marks made, the level of mastery it takes to be a fly cast painter like Ben Miller, and the extraordinary art that emerges from the other side of the painted surface (yes, after the painting is finished, it is flipped around, and the protective sheeting on the reverse of the painted side of the clear plexiglass is a finished painting that looks remarkably like the river painted…), it seems simply wrong, and perhaps more than a touch elitist, to call this complex and sophisticated method of delivering paint “gimmicky”, limiting you from actually looking critically at art and artist.

I don’t know if you are a fan of the late critic Robert Hughes, but I doubt he would have dismissed painting with a fly rod as ‘gimmicky’. Writing about Hughes in The Times of London, Ben Mcintyre wrote:

“For Hughes was, among his many other passions, a true believer in fishing. He was no mere weekend angler, I discovered, but a man who revelled in the strange, transcendental experience of fishing and wrote about it with the zeal of a missionary. The faith of fishing is hard to explain to a non-believer. As an experience it is frequently damp, time-consuming and unproductive. As Hughes put it, “fishing largely consists of not catching fish”. It is essentially a solitary sport, but never lonely.

For many fishermen, fishing is tightly entwined with childhood and the discovery of a sort of quiet mental experience unlike any other.”

Hughes wrote a book on fishing, ‘A Jerk on One End’, and talked about the relation of fishing to art:

“Fishing enabled me to be alone; to dream, yet with senses on full alert…Though I didn’t really know it at the time, I was getting an education in seeing and discriminating. To fish at all, even at a humble level, you must notice things: the movement of the water and its patterns, the rocks, the seaweed, the quiver of tiny scattering fish that betrays a bigger predator under them.”

The Jackson Pollock/Thomas Hart Benton scholar Henry Adams got what Hughes was saying in a wonderful essay he wrote on Ben Miller:

“When Jackson Pollock first exhibited his paintings, they sent out a palpable energy quite different from a traditional Renaissance painting. Viewers were blown into another zone of consciousness. We get this same feeling from Ben Miller’s work, which transfers our usual ideas about representation into something different—a form of awareness that’s strangely abstract, mystical, and even a bit religious.

In Ben Miller’s case, this is very much the product of the way he brings together two art forms that seemingly stand far apart: fly-fishing and painting. We tend to think of fly fishing as a sport, as a physical activity, although in fact, it has a mystical, shamanistic quality as well—and in fact this seems to be the thing that fishermen most prize even more than catching fish. It’s an art form.

… fishing also has a mystical aspect, and this is the central theme of the first great classic of fishing literature, The Perfect Angler by Isaac Walton, who was a student and follower of the priest and metaphysical poet John Donne. Indeed, it’s been suggested that the title of the book is a play on the phrase “The perfect Anglican.” Two themes run through the book: the notion that fishing provides release from the stresses of life because it brings the fisherman into contact with the pastoral beauty and healing powers of nature; and the notion that fishing has a contemplative aspect, and involves entering a state similar to that of religious devotion or prayer.”

Hughes statement “you must notice things” leads us to another argument for Ben Miller’s importance. Throughout art history artists have presented different ways of seeing the world. A hallmark of modern art is the artist’s awareness of how human perception and cognition factors in to seeing – the opticality of Impressionism, the cognitive, almost Kantian structure in Cezanne, multiple perspectives in Cubism, and arguably the atomism of Pollock. These are all ways of seeing the world and then communicating that vision in art.

Ben’s years of fishing and hunting trained him to see the world differently than most artists before him. He sees in a more primal mode that relates to man’s long history as prey and predator. When I am with Ben on a river, he points out trout beneath the surface of the water that I don’t see. When we are driving through the mountains of Montana, he points out elk, antelope and deer amidst the trees and rocks. He takes this mode of seeing into each of his many-houred fly cast sessions, constantly looking at the river swatch before him, choosing which fly brush to use to make the right mark, which colors to mix to replicate the color before him, and which set of casting marks to convey the constantly moving body of water before him.

This prey/predator way of being, this more “animalistic” way of seeing ourselves, is dealt with in a recent book by Melanie Challenger, ‘How to Be Animal – A New History of What it Means to be Human’, which has been described as “A searching examination of our intellectual divorce from the natural world.” In a review of the book, JoAnn Hart writes:

“To call someone an animal is considered a grave insult, but it is also the truth. We, the humans, we are all animals. It’s not something we like to admit, but if Melanie Challenger is correct in her thinking, embracing our animalness will help humanity better deal with new gene technologies combined with the imminent and ongoing perils of the natural world.”

Another reviewer, Stuart Kelly, writes:

“Its basic argument against “human exceptionalism” can be broadly sketched as covering three areas. All stem from one contention: that humans have, in some rather unexplained fashion and by unfathomable processes, decided that we are disconnected or apart from the natural world. The consequences of this “othering” of the natural and the dislocated nature of the human – between the beasts and the angels, if one wants to phrase it theologically – is that our relationship with other living things on the planet is out of kilter and destructive; that it has a perceptible diminution in the physical and mental well being of humans; and that in our quest to distance ourselves yet further from the natural we may be unleashing horrors as yet unforeseen or imaginable.”

Jerry, so many of the things you have written over the years suggest you could, if you chose, look at Ben Miller’s art and see something significant:

“I'm not for or against … any medium or style, for that matter.”

Except for painting with a fly rod?

“Appropriation is the idea that ate the art world. Go to any Chelsea gallery or international biennial and you'll find it. It's there in paintings of photographs, photographs of advertising, sculpture with ready-made objects, videos using already-existing film.”

Is Ben’s art an opposite of appropriation?

“Everyone goes to the same exhibitions and the same parties, stays in the same handful of hotels, eats at the same no-star restaurants, and has almost the same opinions. I adore the art world, but this is copycat behavior in a sphere that prides itself on independent thinking.”

Perhaps there is a built-in city-fed art-world elitism that needs to be looked at, powerfully disconnected from the natural world?

“Art is changing. Again. Here. Now. Opportunities to witness this are rare, so attend and observe.”

Yes – “rare, so attend and observe.” You write about the important decades – for example, the 1940s. Is it possible this moment in history and art history may be as auspicious? That we are on the edge of a new zeitgeist that presents a new kind of artist, one that looks out at nature more than into mind, and uses mind to create tools to make art, not to be the subject of art? A new artist for a new zeitgeist who is sophisticated but also a populist, an artist who is a fisherman and hunter and understands the world of prey and predator, who sees being human as also being animal?

I would argue that Ben is a new American artist coming out of a demeaned older American artist tradition, the American Wilderness tradition, powerfully connected to Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and John Muir in its reverence for nature; a reverence sorely needed in the midst of climate change, disrespect for our environment, and time spent in front of computers, smart phones, and television screens.

Perhaps that tradition was properly demeaned, as its best artists, Charlie Russell and George Catlin painted (beautifully) elk, bison, rivers and mountains (and a bunch of cowboys and Indians), in a style which borrowed heavily from European realism; a style which could not cut it in the 20th century age of modernism.

Ben breathes new life into this tradition in a powerfully original and unique way – Charlie Russell and Jackson Pollock united. At this point, no one does what he does (Ben and I joke that in the future we will see fly-cast painters along rivers as one sees fly fisherman now).

You can put a Ben Miller painting in a room with a fly fisherman from Idaho and a sophisticated New York City art dealer, and they both can appreciate it.

As I have written previously, I believe Ben Miller is an artistic genius, different in significant ways from artists before him. He powerfully comes out of two important artistic traditions, American Wilderness painting and the breakthroughs of Jackson Pollock. He is positioned uniquely, to his credit, outside of a third, the dominant art world of today - filled mostly with artists who make paintings to illustrate the ideas in their heads.

If I am right, perhaps someday you will amend your aforementioned quote, and say something like:

“Just as Pollock used the drip to meld process and product, Frankenthaler used stain to unite paint and ground, Richter 'found' and used the smudge and the blur to ravish the eye, Miller uses the animated mark to merge nature and pigment, signaling a new interest in the world as more animate than material.”