About the Author:

Joe Gioia was a prolific and widely published photographer, writer and critic. He was a good friend and a great writer - he is missed.

Ben Miller’s Art of Dry Fly Painting

By Joe Gioia

In English, the word Art is lent to any practice that isn’t exactly work, or merely play. Central to every one – be it painting, archery, dance, or motorcycle maintenance – is a dedication to craft that goes beyond casual effort. Also necessary is an engaged use of the materials at hand – pigment, a stage, the muscles in your arm - to produce an object or an experience that brings a reaction, possibly of wonder or recognition, in the artist first of all and then, maybe, in others too.

If from a distance you see Ben Miller working on a painting, you can be excused for mistaking the art involved. Miller creates his pieces outdoors, on the banks of some of the wildest rivers between central Washington state and Colorado. He stands about twenty feet away from a work-in-progress and paints with sharp, repeated strikes from the end of a 13-foot casting rod and nine feet of line.

Miller applies what he’s learned about the ancient and honorable art of fly-fishing to the spontaneous act of Action Painting. It’s not that odd, if you think about it. Both the fly-caster and action painter perform in a constant now, paying close attention to colors and shapes as they arise. Both artists strive to make skillful marks, be they ripples in water or bolts of color; to attract attention; to connect to something alive outside of themselves.

No, not strange at all. But Ben Miller thought of it first.

Anyone who fishes for trout will tell you that, if you have the eye to see it, a river is an immense and subtle drama. Tom Rosenbauer, author of Reading Trout Streams, advises his readers to (his emphasis) “See through the water … Imagine yourself sinking below the surface, in that noisy world filled with silver pearls of air. Now you see [the trout’s] rock. It’s shaped roughly like an equilateral triangle with each side about two feet long …

“And now you’re reading a trout stream.”

It should come as no surprise that Rosenbauer is one of Miller’s favorite authors. And if Miller “reads” rivers, his paintings, each made over the course of a day spent in an absorbed evaluation of his subject, is a recital in color. The specific text under consideration is about fifteen feet long, stretching between the near and far banks, The splashes and contours of his contrasting colors express the infinite, chaotic dashes of the river itself, its bright surface reflections and ripples down to the rocks, logs, and gravel lining its dark, stony bed.

The text is different every day. Once choosing a spot, and after judging the light and weather conditions, Miller selects tubes of paint appropriate for conditions from dozens he keeps in a big plastic bin in the back of his truck, dropping them into a wicker fisherman’s creel he hangs off his right hip. Fundamentally a colorist sensitive to subtle grades of tones between dark brown and milky green that predominate in the water, Miller squeezes the chosen paints onto a slim aluminum case that opens like a book, his working palette - a box made to hold the array of hooks-disguised-as-insects that are the fly fisherman’s main weapons.

Miller uses a conventional paintbrush to mix his pigments. After that, he works with an array of finger-sized bits of fabric and cord, an assortment of distinct shapes of his own design that he ties to the end of his line. Miller uses the brush to load paint onto the particular “fly” he’s chosen to leave a signature mark, long or short, thin or dense, when it hits his “canvas”. The target is a clear sheet of Plexiglas, sized 3’ x 4’ or 4’ x 8’, Miller leans against an aluminum A-frame easel standing at ground level.

To do one painting, which he accomplishes in a single day-long session, Miller needs to cover twelve, or thirty-two, square feet of surface with succeeding layers of marks only inches long and wide. This demands constant effort. Eyes focused on a single point, he rocks forward and back, both hands on his one of his casting rods, (he uses mainly a nine-foot Winston Boron and, for more emphatic marks, a thirteen-and-a-half-foot Winston Spay) bringing force to his brush strokes in broad swinging arcs.

Miller uses an astounding sense of control gained from studying the fly caster’s art. He hits his distant mark, over and over again, for hours, in weather conditions bright and hot, overcast and cold, with no obvious fatigue. This is evidence of a lifetime spent outdoors in a singular pursuit.

Now in his early 40s, Miller grew up in central Washington state, learning to fish from a father whose approach to the angler’s art involved keeping a journal, something Miller now does for each day spent painting. An early aptitude for drawing led to a college art major and, with an education degree, a job teaching art at his hometown high school. After twelve years of that, Miller says he was ready to move on.

Outside the classroom, while painting oil-on-canvas, photo-realist depictions of trout in their natural habitat, he became obsessed, he admits, with ways to express the thin, uneven bars of sunlight he saw waving across rocky river bottoms. One night, inspiration struck. Instead of painting the forms by hand, he reasoned, maybe they could express themselves through the same forces of liquid motion, something like a velocity of splashes, found at the river. He set up a canvas in his backyard, daubed paint on an old sock tied to the end of a line run through a nine-foot rod. Giving it the lift and force needed for heavier bait, say a frog lure, he cast and hit. That first mark was too big, Miller says, but good enough to validate the idea.

It was obvious soon enough that stretched canvas would not bear up to the new technique’s steady barrage, so he switched his medium to high-impact Plexiglas. Now the problem was that oil paint wouldn’t bond cleanly to the new surface, so Miller moved on to acrylic.

To create the varied marks (what he calls ‘hits’) for his new work, Miller then began to experiment with various materials – wool, cotton, rubber, plastic, and nylon – shaping loops, lines, balls, and knots designed to deliver paint in distinct patterns. These were steadily refined to form what Miller calls his fly brushes. They are alternative life forms in mostly natural shapes, creatures with long feelers, short wings, and fat thoraxes - a private entomology of special effects.

Miller’s brushes fall into main types: one for the varied courses of water, the other for the many shapes and contours of rocks. Water flies will vary by the amount of paint they can hold, how forcefully they leave a mark (active water needs sharper and broader hits from several strands at once, smooth flowing water needs applications from single lines). Rock flies, large and small, deliver concentrated shapes.

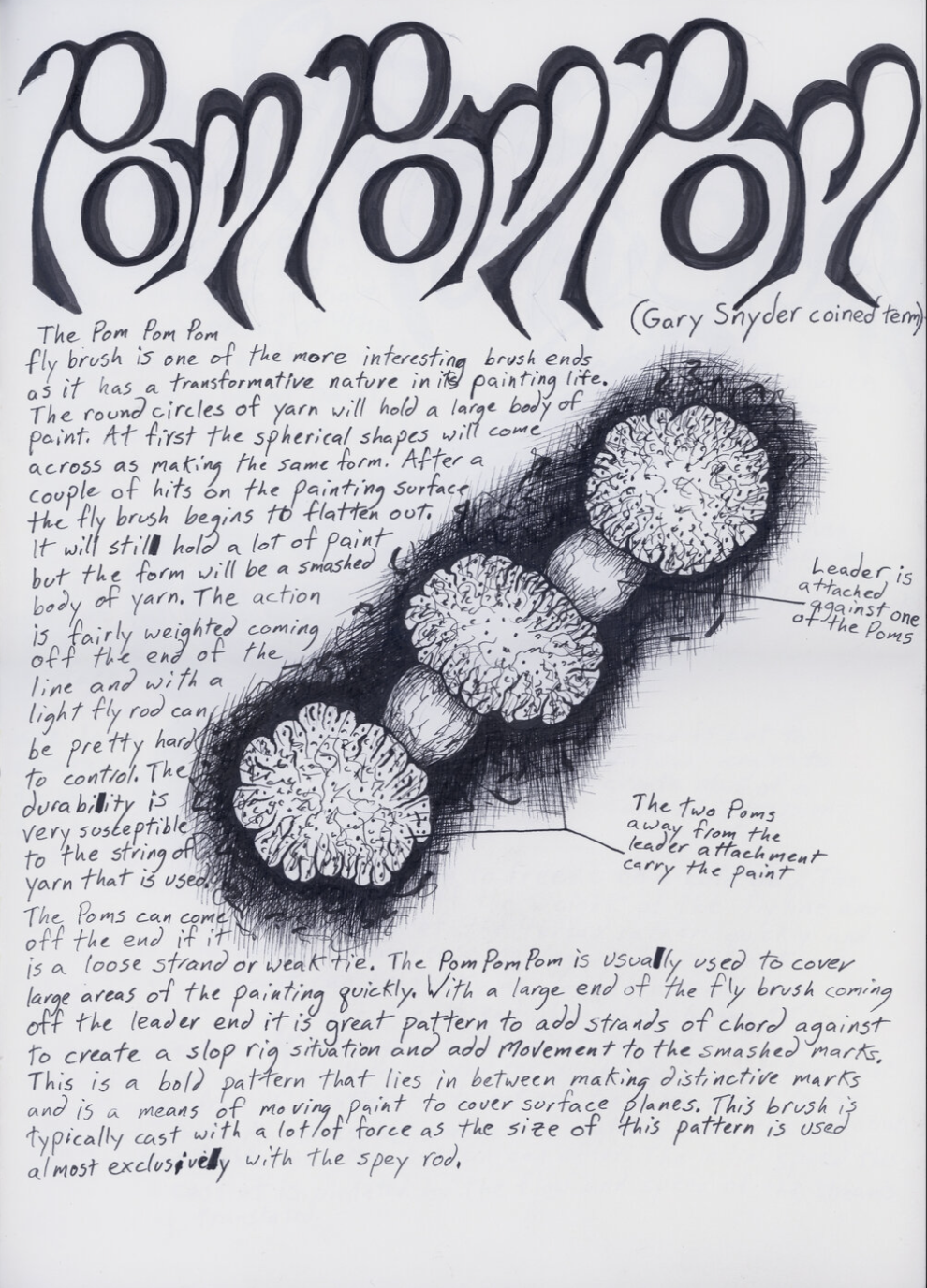

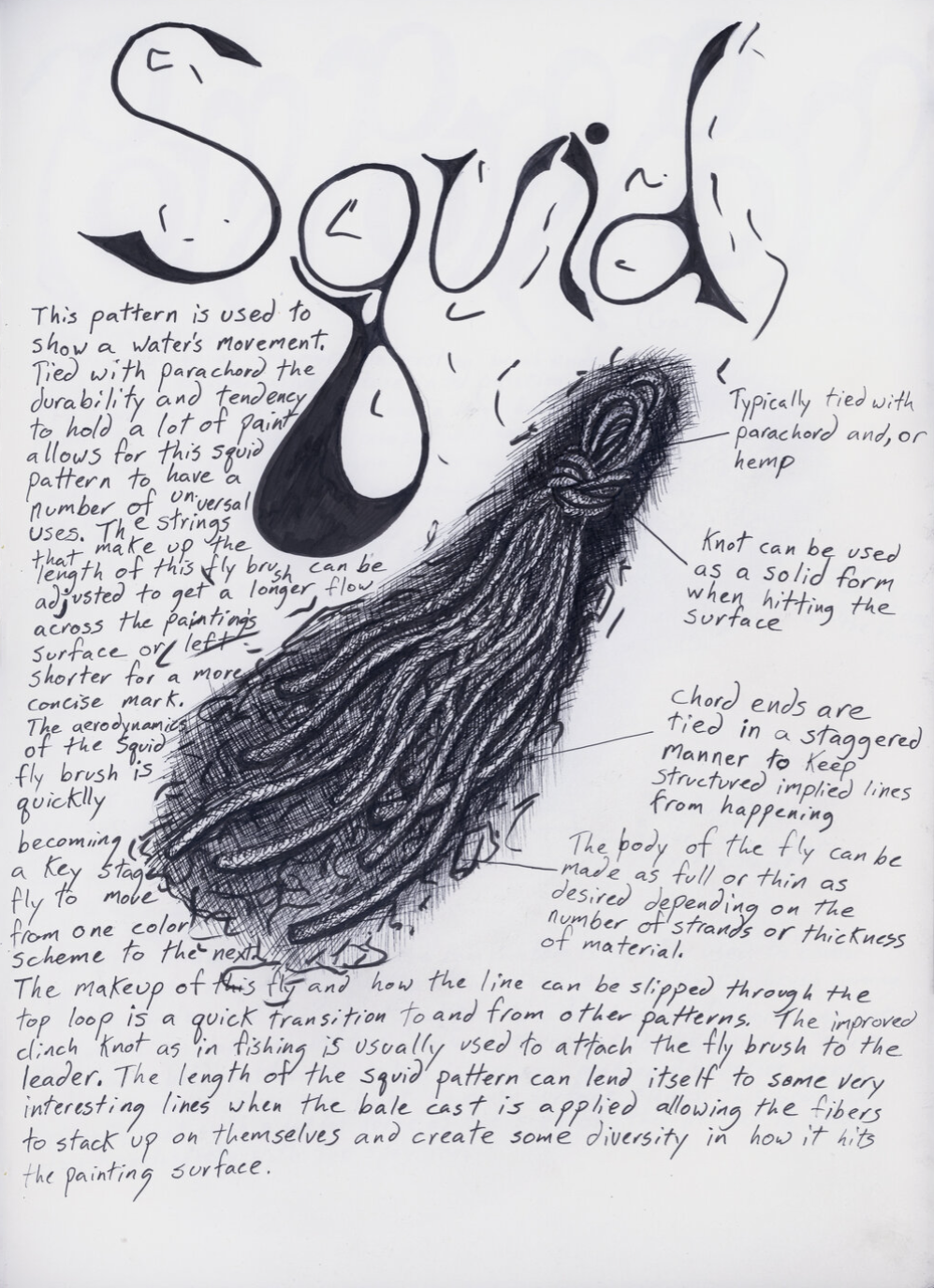

In the best angler’s tradition, Miller names each of his fly brushes. Some are obvious – Squid, Caterpillar, Cocoon, Worm – others fanciful: the Anarchy Beetle, Slop Plug, Toobal, Voop-Voop, and Major Tom’s, to mention only a few. Miller draws each one in a large sketchbook, adding a lengthy notation of what each is for and how it works.

Rock brushes, like the Cocoon are rounded wads of yarn, strips of rags, or cotton pom poms Miller finds at fabric shops. They need to express different shapes, round or hard-edged, and some, like the Anarchy Beetle and Voop-Voop, have attached loops that add surrounding lines to suggest shadows.

Miller uses strips of nylon snipped from stockings that he knots as needed to express the running current between surface splashes and bottom rocks. The Span Band holds a lot of paint and expands during the cast to leave the longest, softest, and cleanest hits. River grass and algae that cling to the riverbed call for bristlier brushes. Here Miller uses knotted hemp fibers he calls the Monocone, or a Chuter, a short bouquet of feathers bound in a rubber tube.

You need to go back pretty far in history to find painters who had to make their own brushes. And though the classic mid 20th century action painters sometimes resorted to ad hoc alternatives – sticks, knives, rags, even shoes – no artist on record has spent the effort to make a range of unique brushes, each applying color in a distinct way. So, maybe without intending to, Miller filled a blank space in the history of Modern Art.

Miller’s paintings, like the rivers themselves, are many-layered and long-lined. While his preparation is calculated, the execution must be spontaneous. He must first find the right spot, then read the river and the day. Clear skies drop different colors in the water than cloudy ones. Bright mornings can become overcast afternoons, and the painting must change accordingly. The water is also subject to change, especially in the early spring when, a warm morning can send muddy snowmelt churning down what was only an hour earlier a placid and pristine waterway.

Miller paints on what will become the back of the finished piece. When turned around, the first strikes of paint represent surface reflections and whitewater rills. These highlights are then backed by successive color layers of deeper and darker forms, notes of the sky, grass, gravel, leaves, and rocks.

Those first strokes are done with long-line flies, either a single Worm, or a multi-armed Squid, maybe a Whisper. The larger ones hold more paint after the first hit, and Miller will reapply them two or three times in startlingly accurate patterns before loading on more color. The work grows line by line, layer by layer, the rough impact of paint on Plexiglas ably reflecting the shapes of water running over and around stones and rocks. When completed, a painting fits neatly into its immediate surroundings, as if Miller has sealed off a portion of the place and day that he takes with him when he goes.

In winter months, bystanders generally presume he is fishing out of season and will contact law enforcement. Once summoned, the authorities think his work is pretty cool, and he’s never been told to move on. Sometimes, though, nature intervenes. Cattle are frequent visitors. Last year in Yellowstone Park, he had to give way to a small herd of very large bison that ambled over and sat down near enough to impel a retreat to his vehicle for a couple hours. By the time the animals left, he says, the river had turned wild from snowmelt, which of course required a radical redo of the day’s painting. No matter, Miller’s stated goal for his work is to mark down the truth of a river, not something he thinks it should be.

In this sense then, Miller’s action paintings are not abstractions at all but a collection of moments that reflect the onrushing life of things in constant, and constantly varied, collision - a complex snapshot of one place on a particular day. If Miller’s paintings express any particular idea, it is that small parts of the world can hold our deepest attention; and looking closely offers great rewards.